Just a job: Gendered militarism as everyday normality in Germany

By David Scheuing

Institutionally the military is one of the last “bastions” of male dominance. The idea of strength and virtue is still attached to the male body and the male soldier. As the German army (Bundeswehr) tries to find new ways of recruitment in the post-conscription-era of today, gender politics become a major fact to recruitment efforts. Other than the contentious “adventure-camps for minors”1 2, targeted advertisement of the Bundeswehr aims at recruiting specialised audiences.3 In this gender mainstreaming becomes – in the disguise of diversity politics – a face for legitimised and normalised militarisation, enabled through its high presence in the everyday life. The issue taken up here is therefore not so much with gender-equality in a public sector, but with how this becomes a vehicle to present the military as no different than any other job. It is the normalisation of militarism that is challenged here, not gender equality.

A short history of gender equality in the German military service

With the “Gesetz zur Gleichstellung von Soldatinnen und Soldaten in der Bundeswehr”4 (SGleiG) taking effect from 2005 on, parliament formally created equality between men and women in the army with regards to ranks and careers. This followed a decision by the European Court of Human Rights in 2000 that the exclusion of women from the German military and the discriminatory career paths therein was unconstitutional. Nonetheless, a variety of issues are not dealt with in the law, such as disabilities or identities and sexualities beyond the binary divide. Ever since these legal incursions into male territory have been made, “men rights” activists interpreted them as “experimental labs for the ideology of gender mainstreaming”. As these activists still believe “war to be inevitable” and “tough” they cannot be ready to accept female soldiers, even less so on “unequal terms”, what they see as unfair favouring of women in the army, from tasks to job promotions. The truth, however, is a fairly bitter one: of the actively serving soldiers, only a minority are women (roughly 10%, with a huge bias towards the non-fighting groups such as nurses (37% of total) and civilian workforce) and despite equal opportunities to career paths, only very few women do get promoted.

An institution in reform

Since the early 1990s the Bundeswehr has seen major reform projects: Campaigns abroad in the wake of NATO's restructuring, gender equality policies, since 2010 the big structural reform, limiting the number of armed and civilian personnel and lastly the end of conscription.

Advertising war: Casualties of casualness

The military is increasingly launching advertisement campaigns across the country in order to fill the ranks. Since the Bundeswehr is aiming to be an equal-opportunity employer (and since it has to be so, according to German non-discrimination legislation), the campaigns also increasingly target women. What has to be considered though is the level of proficiency in displaying the army as “just another job”.

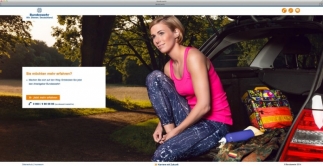

In 2014 the Bundeswehr launched a high profile advertisement campaign, that came to a grinding halt after only a few days. The large posters and ads launched depicted a number of alleged “everyday situations” with a seemingly seamless integration of the military into them. The campaign aimed to provide the narrative to avoid estrangement of the citizens from the military – in this following an age-old idea of the German “citizen in uniform”. This integrated army, however, was conceived in the age of conscription: the German demos was made to believe they still had the control over their army, an important narrative amongst heightened fear of a re-armed Germany in the 1950s.

In times of a volunteers' army, this almost generalised normality of army presence in society is an increasingly important aspect of the job description prior to signing up. Here the army produces its inevitability via broad social reconnaissance and acceptance. None of the individuals depicted has to give up their individuality as social beings. All can be women, mothers, leisure time enjoying sunbathers and soldiers at the same time. The homepage, where this campaign was published, was indicative: www.frauen-in-der-bundeswehr.de5 which translates to “women in the army”.

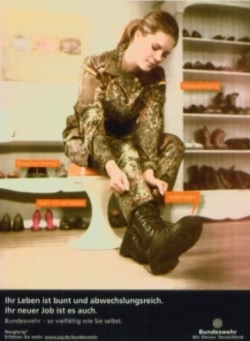

The campaign displayed women (see the first three images), all busy but happy in what they are doing: opening a wardrobe, tying their shoes, or going to shop with their children. Following a similar prior campaign from 2013 where the narrative was a shoe-centered approach (see the image on the right) about the variety of things that can be done everyday6, this campaign came without words. The message had to be found in the image. And it was to send a clear message: The Bundeswehr is in the everyday, and it is a job no different from any other. Thus everyone can do it and can still enjoy this. This definitively contrasts sharply with earlier campaigns by the Bundeswehr which clearly highlighted the adventurous, uniformed and gadget-fond dimensions of army life (see the image below).

Additionally, here the subtle message about a normalised place of the army in the middle of society is disguised by an approach of a more gender-sensitive campaigning of the army. The thorny issue of equal-opportunity in a field of militarism has to be addressed though: neither is it the fault of any of the women in the advert, nor of any soldiers fighting for equal opportunities in the army, that this message is a hideous attempt to normalise armed violence into society. The campaign brings together two very powerful narratives that assist each other to “break up negative sides” in each other. On the one hand, we find the modern woman confident of her beauty, her life and her occupation being able to do several things simultaneously (raising kids, training her body) and on the other hand, there is the soldier (in her and in general). The campaign frees the image of the soldier from such of a cloistered body, subject to much external (state) influence and thus normalises the job into becoming just another job; and on the other hand it presents a powerful image about how women should be: caring, loving, dedicated, but strong mothers, with a generalised shoe fetish and a stark emphasis on body perfection (dressing up, training). Here, patriarchy has found a door to link a fight for gender-equality and everyday militarism.

Perhaps it was perfect that the campaign did not only end soon because it was decried by many activists and journalists on the grounds of its antiqued role model idea about women, but also because of an infamous “technical error”: on the social media platform Facebook the campaign was linked to a picture of “Zewa”, a cleaning tissue for household purposes. This effectively ridiculed every effort of the Bundeswehr to secretly sneak “harmless” campaigns into everyone's consciousness. Nonetheless, more of these campaigns are probably coming up. The militarism embedded therein will have to be resisted, not gender mainstreaming.

David Scheuing is a graduate student of Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Marburg, Germany. He has been a member of local struggles to fight for a peace clause in the university regulations. David is also a member of War Resisters' International (WRI) network and a former intern at WRI office. He has edited the Miltiarisation of Borders issue of the Broken Rifle, WRI's triannual magazine. David is interested in the role of societal militarisation in - but not limited to - Germany.

-------------------------------------------------------------

4 Law to establish equality between male and female soldiers in the German army.

6 cf. Spiegel 2013

Countering Military Recruitment

WRI's new booklet, Countering Military Recruitment: Learning the lessons of counter-recruitment campaigns internationally, is out now. The booklet includes examples of campaigning against youth militarisation across different countries with the contribution of grassroot activists.

You can order a paperback version here.