Do you really want to do what counts? German recruitment and the dangerously silent opposition

By David Scheuing*

Germany's Bundeswehr (“Federal Army”)1 has started renewed efforts to recruit the upcoming generations of soldiers and military personnel (including civilian roles) more generally. This effort is most visible in a series of ads and poster campaigns run throughout Germany in the last years. Since Germany stopped the forced enlistment in 20112 there have been a lot of “productive” recruitment efforts. Starting with rather ”fun“ campaigns advertising off-schedule Bundeswehr trainings in 2009, the military continued with two high-level campaigns on female recruitment, and one aimed at general recruitment in the early 2010s. Another campaign - particularly aimed at civilian staff - (2014) followed suit. This illustrates how the German “Verteidigungsministerium” (“Defense Ministry”) goes for an “all-In” approach to recruiting new personnel.

The new campaigns of 2015 and 2016, however, show a level of professionalised norm lending in armed forces recruitment from around the world formerly unseen in Germany. Yet there is little palpable resistance to this – apart from the occasional articles or ad-busting.

In this article I briefly highlight where the belief for the necessity of these recruitment strategies comes from, and how it has been rolled out, with a special interest towards the targeting of young people. Lastly, I look at what antimilitarist answers have been (or failed to) and what we could be aiming for.

Recruiting a new army

The campaigns described and approached in this article do not just happen out of thin air. Throughout the existence of the Bundeswehr, there have been advertised recruitment efforts to make a military career appear attractive, even while conscription was taking place. Even when young adults did not have to be targetted directly because of conscription, there were efforts to bind them to the army after their time as conscripts had ended. These campaigns usually praised a specific career within the army ranks. Parallel to this, the Bundeswehr were also outsourcing “non-military” roles traditionally filled by military personnel to civilians.

This shift towards ”efficiency” based ”civilising” of the staff occurred alongside bigger shifts in the overall outfit of the Bundeswehr. Instead of being an entirely independent block in the state's general functionality, external advisers on military technology gained greater influence as well as the outsourcing of – e.g. civilian drivers – personnel began.

When the German government reduced the staff numbers of the Bundeswehr in the early 2000s, the debate as to whether to put a “halt” to conscription took place within ministry circles, as a viable option to reduce numbers. This was contrary to conscientious objectors' (COs) efforts to finally bring down conscription once and for all, but some went with the promotion of a conditional halting of conscription as the lesser evil. When – more by surprise, than by actual transparent planning – the German Defense Secretary von Guttenberg announced the halting of conscription, the army had to quickly learn from recruitment experiences abroad.

In what we can see nowadays, the practice of campaigning, opening up flagstore-like recruitment bureaus, strengthened efforts to approach pupils in schools, as well as “adventure camps” and the like, the Bundeswehr seems to have sought inspiration from the US and UK armies, among others. For example:

-

Officers, posing as simple “information officers for the youth”, are being deployed to schools with lots of material and ideological legitimacy to actively advertise the Bundeswehr to young people (even though they are not allowed to properly recruit them). They claim to act in the name of peace, yet the necessity to wage war is never in question with them.

-

Recruitment offices are opening up in Germany even outside of barracks (“Kasernen”), where they were positioned more traditionally.3 This is being complemented by the “Tag der Bundeswehr” (Annual Day of the Bundeswehr) as part of which which – from 2015 onwards – people can enter barracks, watch and touch equipment and in some cases were allowed to aim with unloaded weapons (even children, see below, footnote 16), etc. It is a totally different approach to publicly legitimising the necessity of an army than the old “citizen in uniform”-discourse which was embodied more directly by recruits. Now it needs to be an invitation to “visit” the barracks and HQs.

-

Large advertisement campaigns, increasingly using multimedia and being spread through a large number of networks, are launched. A more in depth description follows below.

-

The ever increasing “game-ification” of war, its “gadgeting” and its continued proliferation,

-

becomes part of a more unified “security discourse” in which the discussion of a “use of the Bundeswehr in the interior” becomes part of political debate again – even though the constitution rules out any internal deployment if not for defense purposes in times of attack or in crisis situations, where the Bundeswehr is sought to help keep up “public order”.

These changes to the recruitment and equipment of the army integrates into a new vision of the German army as a deployable and actively intervening army, attractive to general warfare efforts. For this it needs the personnel, and so targets young people in a more coherent and all encompassing manner than ever before.

The campaigns in details

As the Bundeswehr was not used to having to actively seek its recurits, the Bundeswehr had to develop new recruitment strategies from scratch.4 Particularly so, as it could not build on a stable degree of general militarism in society. Thus, in early years prior to and directly after the halting of conscription, these attempts to recruit were pitifully awkward at best.

The Bundeswehr's own youth homepage – and section – co-organized (and still continues to do) bootcamps in cooperation with one of Germany's best known youth magazines. The “BRAVO” and “treff.bundeswehr.de”5 organised a camp for the first time in 2009, already before the halting of conscription, targeting pupils, with the aim of the young people attending becoming more attached to the “values” and “procedures” of the Bundeswehr, emotionally and from embodied experience. This caused major outcry from childrens' rights activists and was also taken up in the media, but was soon forgotten.6 However, the debate resurfaced in 2012, again advertising “Sonne, Strand, Sport, Abenteuer und viele Informationen rund um die Bundeswehr “ (“sun, beach, sports, adventures and plenty of information about the Bundeswehr”).7 The camps continued to be used as a tool for recruitment in 2014 and ongoing8, despite the critiques of it.9

The Bundeswehr's own youth homepage – and section – co-organized (and still continues to do) bootcamps in cooperation with one of Germany's best known youth magazines. The “BRAVO” and “treff.bundeswehr.de”5 organised a camp for the first time in 2009, already before the halting of conscription, targeting pupils, with the aim of the young people attending becoming more attached to the “values” and “procedures” of the Bundeswehr, emotionally and from embodied experience. This caused major outcry from childrens' rights activists and was also taken up in the media, but was soon forgotten.6 However, the debate resurfaced in 2012, again advertising “Sonne, Strand, Sport, Abenteuer und viele Informationen rund um die Bundeswehr “ (“sun, beach, sports, adventures and plenty of information about the Bundeswehr”).7 The camps continued to be used as a tool for recruitment in 2014 and ongoing8, despite the critiques of it.9

In addition to the open recruitment and advertising, the Bundeswehr have been quietly sponsored sports events and from as far back as 2011, to appear more favourably in the public, as Michael Schulze von Glaser then wrote.10

When, in 2015 the Bundeswehr rebooted their “Grundausbildung” (basic training) campaigns, they were suddenly built not only on poster ads, but also on a modernised homepage theme, an integrated use of social media (twitter, facebook) and a newly developed ”camouflage pattern”. This ”modernised reboot” brought with it two campaigns so far:

-

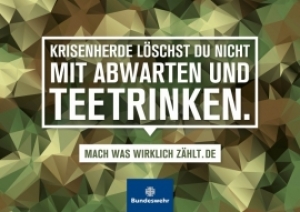

the “Tu was wirklich zählt”-campaign in 201511

-

and the ”web video series” recruitment efforts of ”Die Rekruten” in 2016.12

First, in 2015 Germany awoke to a new reality of aggressive advertising of the military. Making use of catchy phrases and intuitive comparisons, they managed to get in peoples' heads. The idea that conflict would need active military engagement had finally arrived plain and unashamed in German public life.

In that the campaign had been accompanied by a refurbished homepage under the URL “www.machwaswirklichzaehlt.de” (“Do what really counts”) it replicated strategies of modern recruitment learned from other countries' experiences. The campaign built on the narrative that only military action was “what really counts”. The implicit tactical messages rose to prominence.

The homepage closed with a map on which all the recruitment centres were mapped, a feature also new to the German public: that fancy official recruitment bureaus might soon be popping up in shopping lanes and in midtown, not hidden away in the mazes of bureaucratic recruitment practices.

Furthermore, these new recruitment strategies are built on stratified beliefs and class clichés. In particular, in the 2016 campaign a dangerously simplistic overlap between class stereotypes, age stereotypes, game-ification of war, and the appeal for “adventure” was used.

The above poster from 2016 bears the caption saying: “From November on we will play outside”. The implicit message is clear: what you train on your personal computer can as well – and even better so, it seems to say – be applied “outside”, indicating the training compound and then in even bigger terms, the greater world. You can see a setup of two computer screens, a gaming keyboard and mouse (which can be understood by insiders from the “gaming community” approached here, as the brands are not covered up or removed), two opened cans of a contemporary “power drink” advertised to the youth (even though one has to guess, as the brand side is facing away from the spectator), and a dark outer environment, indicating a focus on someone's gaming obsession. This poster bears a number of references, none of which can easily be understood if not by the community, and/or people interested in these circles, of gamers.

The above poster from 2016 bears the caption saying: “From November on we will play outside”. The implicit message is clear: what you train on your personal computer can as well – and even better so, it seems to say – be applied “outside”, indicating the training compound and then in even bigger terms, the greater world. You can see a setup of two computer screens, a gaming keyboard and mouse (which can be understood by insiders from the “gaming community” approached here, as the brands are not covered up or removed), two opened cans of a contemporary “power drink” advertised to the youth (even though one has to guess, as the brand side is facing away from the spectator), and a dark outer environment, indicating a focus on someone's gaming obsession. This poster bears a number of references, none of which can easily be understood if not by the community, and/or people interested in these circles, of gamers.

-

Heavy referencing is made to “war games”, “military games”, or “ego shooters”, as the caption together with the picture implicitly ask for someone gaming on military issues (such as the above mentioned war games) to step out of the “cave of the gaming nerd” and participate “outside”. This in itself is a problematic reference because it asks for youth trained in aiming at virtual enemies to train in “real life” with “real weapons”. The outside-reference is directly loaded with this assumption.

-

Secondly, reference is made to the computer gaming community in general. The setup of the image indicates special equipment “necessary” for semi-professional gaming: more than one screen to monitor all relevant information; specialised keyboards (even if it is only colours, but some also have special keys); special nutrition. This reverberates with the greater “strategic gaming community” as well, as just within the picture at least no implicit assumption about the nature of the game is made, just about the type of gadgets necessary, allowing for considerations about “strategy” as a generally favoured aspect.13

-

The combination of elements is also problematic because it aims at an imagery of a highly specialised “nerdy gaming community” in their own right. With this the Bundeswehr looks for people often disrespected for their hobbies and often enough socially silenced or pathologized (often also as implicitly or prospectively violent youths). Yet, the Bundeswehr does not aim at the societal de-marginalisation of these individuals, rather it builds on the continued self-identification of parts of the approached youth with this portrayal. Here the Bundeswehr uses a tactic of binding the highly individualised and in this potentially rebellious youth to a call for general discipline and “comradeship”.

In this sense, the campaigns need to undergo a more thorough critique and countering in public space as much as in classrooms or any other public or private life. A dissection of the visual/imaginary-intellectual overlaps is necessary if these strategies of military actors should be countered and de-legitimized.

It is too silent! Yet...

The response to the renewed efforts made by the Bundeswehr, however, has been a resounding silence so far. Antimilitarist and nonviolent activists published statements and started campaigns against it (DFG-VK, Pax Christi, BSV, etc.)14 but the most direct form of intervention was a spree of ad-busting (www.machwaszaehlt.de) by the Peng!-collective in Berlin in 2015.15 So far they have been the only real cases of outspoken resistance against these campaigns and their wider reverberations.16

statements and started campaigns against it (DFG-VK, Pax Christi, BSV, etc.)14 but the most direct form of intervention was a spree of ad-busting (www.machwaszaehlt.de) by the Peng!-collective in Berlin in 2015.15 So far they have been the only real cases of outspoken resistance against these campaigns and their wider reverberations.16

As much as we see the Bundeswehr learning from recruitment strategies in other countries, we need to acknowledge that the German antimilitarist movement's learning curve has not been as steep. We can and should react. German antimilitarist answers need to be informed by but still be independent of British, US-American, or other antimilitarists' or counterrecruiters' efforts to counter the efforts of recruitment and everyday militarisation. Yet, first we need to learn, connect, and practice active “counterrecruitment” in Germany. The more we are, the better, and we need to continuously build our base. Practical considerations need to be, how we can build knowledge and information bases to spread the practical experiences made as well as learn from successful “countering”. Figures such as that a soaring number of 19% of German pupils believe the Bundeswehr to be a source for good employment should teach us the necessity to fight back!

On the other hand, we need to think about action more than reaction: If the military enters the schools, why are we a step behind to do so ourselves? Yes, we can counter what is endangering our future, but only if we are a step ahead! We cannot let the military have the lead in active “recruitment”. Peace and nonviolence means we need to educate the youth more thoroughly here. Possible steps forward could be:

-

renewed efforts to getting “youth information officers” out of schools (as has happened in North-Rhine-Westphalia recently, even if indirectly)

-

Active nonviolent trainings linking up with other trainings such as “Anti-Bias” work, “antiracist” or “antifacist” educational work or broader “antisexist” initiatives.

-

Develop, advertise and implement alternatives to Bundeswehr media and games in schools and beyond (for example the roleplay “CivilPowker”, alternative “fact sheets” etc.)

As part of a wider strategy to fight specialised military influence and to counter everyday militarism, activist work against the recruitment campaigns of the Bundeswehr is necessary. The “silence” of activists in these areas is not total, but we all need to strengthen our efforts to reach out and further the cause of nonviolent peace and conflict transformation.

* David Scheuing is a graduate student of Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Marburg, Germany. He has been a member of local struggles to fight for a peace clause in the university regulations. David is also a member of War Resisters' International (WRI) network and a former intern at WRI office. He has edited the Miltiarisation of Borders issue of the Broken Rifle, WRI's triannual magazine. David is interested in the role of societal militarisation in - but not limited to - Germany.

---------------

1The German „Bundeswehr“ was founded in 1955 with Germany regaining the right to arm a military force after World War II. This followed heavy lobbying from German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and his administration. Not only in kind, but also in major dimensions of its personnel, the Bundeswehr needs to be regarded as a continuation of prior German armies, in this case its direct predecessor, the Wehrmacht.

2The German parliament decided in December 2010 that from 2011 on, recruitment – even if still part of the German Constitution – will be “halted” for an undefined period of time.

3Some recruitment offices remain in barracks.

4Here I will only focus on the campaigns directly targeting the youth to becoming cadets (“Rekruten”). There are, however, a number of motives across recruitment campaigns these days integrating them in one bigger recruitment effort. See for this: Press Information on the 2016 recruitment campaign: https://www.bundeswehrkarriere.de/presse The Bundeswehr admits, that it needs to become a real competitor in the overall scramble for skilled labour in its „Attraktivitätsoffensive“. Here it claims to be a mirror of society and as such needing skills from all societal dimensions. This, however, is a laughably gross misrepresentation of societal reality. See: Bundeswehr (2.6.2014) Die Bundeswehr geht in die Attraktivitätsoffensive. Online at: https://www.bundeswehr.de/portal/a/bwde/!ut/p/c4/DcYxDoAgDADAt_gBurv5C3UhLVRsINVUK9-X3HKww6D4ScFXLsUGK2xJZuqBeuZQ0UzYOJBr5qfzaVE0Hj7iWoIzsVGTVOGuy_QDe048YQ!!/

This links up with broader strategies to see the German army's place in society, such as the “Tag der Bundeswehr” (2015- ) and other initiatives. For this see: Bundeswehr (2.6.2014) Verankerung der Bundeswehr in der Gesellschaft. Online at: https://www.bundeswehr.de/portal/a/bwde/!ut/p/c4/TcgxDoAgDEDRs3gBurt5C3UhBQo0kGoKyPV1NH95-XDCl-DDCTtfghV2ODyvbho3A5mCqkxKxg0J1CZltSw2jg9D0n8nalRr8xljh7tsywsE4Yh1/. For a wonderful analysis about what is wrong with this approach see: Dorsch, Alison (18.10.2016): Global agierender Konzern. Die Bundeswehr rüstet auf im Kampf um Fachkräfte und Anerkennung. In: a&k – analyse und kritik No. 620, pp. 25. Full article nline at: http://www.akweb.de/ak_s/ak620/04.htm (German).

Furthermore, I have criticised the use of gender mainstreaming efforts to normalise militarism in the German society here: Scheuing, David (14.10.2015): Just a job: Gendered militarism as everyday normality. Online at: http://www.wri-irg.org/en/node/25040. For a similar argument see: Madjlessi-Roudi, Sara (18.10.2016): Ein freundlicherer Ton. Frauen erfahren in der Bundeswehr nicht nur Diskriminierung, sondern dienen auch der Legitimation. In: a&k – analyse und kritik No. 620, pp. 26.

5The major sites trained at the youth are „Jugend und Bundeswehr“ (online at: https://www.bundeswehr.de/portal/a/bwde/!ut/p/c4/04_SB8K8xLLM9MSSzPy8xBz9CP3I5EyrpHK9pPKUVL2s0vTUvBT9gmxHRQCeP_yn/) and treff.bundeswehr.de. Both have drawn tremendous criticism in past years.

For a selfappraisal of the “adventure days“ see: BRAVO.de (22.09.2014): Zu Gast bei der Luftwaffe in Italien: so war das Bw-Adventure Camp auf Sardinien. Online at: http://www.bravo.de/sport/zu-gast-bei-der-luftwaffe-italien-so-war-das-bw-adventure-camp-auf-sardinien-334807.html

For a critical account of the mediatised auto-representation by the Bundeswehr see: Vogel, Friedemann/Haberer, Maximilian (2014): "Die Zukunft im Visier - Die mediale Selbstinszenierung der Bundeswehr gegenüber Jugendlichen auf www.treff.bundeswehr.de. Online at: https://www.friedemann-vogel.de/media/texte/Vogel_ZukunftImVisier_MuK_2014.pdf

6For critique see: Ralf Willinger (terre des hommes childrens' rights expert writing for DFG-VK): (25.5.2009) »Bundeswehr wirbt und rekrutiert Minderjährige – und missachtet damit die Kinderrechte«. Online at: https://www.dfg-vk.de/kindersoldaten/bundeswehr-wirbt-und-rekrutiert-minderjaehrige-und-missachtet-damit-die-kinderrechte.

7See: https://treff.bundeswehr.de/portal/a/treff/!ut/p/c4/LYyxDoIwFEW_xQ-wBdIB3SQsLg4uWLdHKbUJfW0eD1j8eNvEe5OznOTIt8xH2L0D9hFhkS-pjb-Oh2Cy8yx2S4Arw8IbOotiPGDaLfJG1kBIqxxKYbLCRLRcyNn6TEfAkUSKxEsxG1E2wk9SV3Xf1U1T_Vd_20FdHlop1d-7ZwkmAhdAaoxnA-ZjZQqhPW6n0w_iiaWg/. Information about the “trip” on BRAVO.de – interestingly on its sports pages: BRAVO.de (06.07.2012): Alle Infos zum Berg-Event. Online at: http://www.bravo.de/sport/alle-infos-zum-berg-event-226957.html

8Bundeswehr has been multiplying its youth actions, aiming to gradually normalise its militarising presence in everyday activities: “Discovery Days” // “Bundeswehr Adventure Games” (2009-2011) // “YES4YOU” campaign – this April 2016 targeting a “girls' day” // “treff.on tour”

9Even the online segment of the rather conservative “focus magazin” felt compelled to denounce this practice: Focus Online (08.08.2014): Kritik von KinderrechtsgruppenBundeswehr wirbt erneut in der „Bravo“ um Nachwuchs. Online at: http://www.focus.de/kultur/medien/kritik-von-kinderrechtsgruppen-bundeswehr-wirbt-erneut-in-der-bravo-um-nachwuchs_id_4047844.html. For a more fundamental and informed critique see: Deutsches Bündnis Kindersoldaten (7.8.2014): Action und Adventure im Bikini? Protest gegen Bundeswehrwerbung im Jugendmedium Bravo. Online at: http://www.kindersoldaten.info/Aktuelles/Action+und+Adventure+im+Bikini_+Protest+gegen+Bundeswehrwerbung+im+Jugendmedium+Bravo.html

10Ibid. writing for Neues Deutschland, reproduced on the web domain of DFG-VK: “(3.3.2011) »Karriere mit Zukunft«. Weil sie dringend Nachwuchs braucht, sponsert die Bundeswehr nun auch Jugendsport-Events wie die »Schul-Liga«. Online at: https://www.dfg-vk.de/rekrutierungen-der-bundeswehr/karriere-mit-zukunft

11This campaign formerly worked on the domain: www.tuwaswirklichzaehlt.de. Since 2015 the main domain has been changed to a more neutral: https://www.bundeswehrkarriere.de/. In a perverse reversal of an active antimilitarist intervention to the opening of a flagstore recruitment office in Berlin, the Bundeswehr reacted with one of its slogans from said campaign which was attacked: “We fight for you being allowed to criticise us”. This slogan aims to delegitimise any fundamental critique of militarism.

12„Die Rekruten“ is a daily „web series of videos“ in the style of a documentary series of Netflix, advertised heavily and based at YouTube. It even plays with their terminology „Eine Bundeswehr Originalserie“ instead of „Eine Netflix Originalserie“...

13The accompanying material such as flyers works even heavier within the language of games. Ranks within the military hierarchy of IT-specialists are referred to as “levels” and it makes the solutions proposed look as if IT-specialised knowledge makes the Bundeswehr able to “fight terrorism”.

14Critical campaigns against the “Tag der Bundeswehr” and other events and practices can be found here e.g. DFG-VK: https://www.dfg-vk.de/pazifismus/call-for-action-keinen-tag-der-bundeswehr; Aktion Freiheit statt Angst: https://www.aktion-freiheitstattangst.org/de/articles/5602-20160611-protest-gegen-tag-der-bundeswehr.htm.

15For reporting on the actions see: JETZT (23.11.2015): Peng! entert Bundeswehr-Werbung. Online at: http://www.jetzt.de/redaktionsblog/peng-entert-bundeswehr-werbung-595196; Direct link to the adbusting homepage: https://www.machwaszaehlt.de

16In 2016 the German army for the first time landed a major scandal in allowing kids to touch weapons on the “Tag der Bundeswehr”. This happened in Stetten, Baden-Wuerttemberg and is currently investigated by the Bundeswehr. According to antimilitarist activists similar incidents happened in the 2015 events as well, but no live coverage of this was made at the time. For critical statements see: DFG-VK (13. June 2016): Grenze überschritten: Bundeswehr ließ Kinder an Handfeuerwaffen. Online at: https://www.dfg-vk.de/rekrutierungen-der-bundeswehr/grenze-ueberschritten-bundeswehr-liess-kinder-an-handfeuerwaffen; Aktion Freiheit statt Angst (15.06.2016): Kinder am G36 bei der Bundeswehr. Bundeswehr lässt Kinder mit Gewehr G36 hantieren. Online at: https://www.aktion-freiheitstattangst.org/de/articles/5615-20160615-kinder-am-g36-bei-der-bundeswehr.htm. Critical campaign on underage recruitment, run by the German Federation against Child Soldiers as “Red Hand”: http://unter18nie.de/; Campaign against Bundeswehr in classrooms: “Schulfrei für die Bundeswehr“, online at: https://www.dfg-vk.de/schulfrei-fuer-die-bundeswehr/.

Countering Military Recruitment

WRI's new booklet, Countering Military Recruitment: Learning the lessons of counter-recruitment campaigns internationally, is out now. The booklet includes examples of campaigning against youth militarisation across different countries with the contribution of grassroot activists.

You can order a paperback version here.