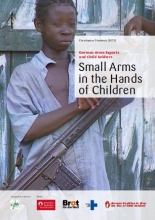

Boko Haram militants have abducted upwards of 2,000 girls in the past two years, some of whom have been forced to become child soldiers alongside abducted boys, reports the human...

Countering the Militarisation of Youth is a project of War Resisters' International | 2017 | All content of this site is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License, unless otherwise stated.

Website development by Netuxo Ltd