Researching Pop Culture and Militarism: What is Militarism? What is Militarization?

Selene Rivas - November 22, 2017

In the previous articles, we talked about how normal is defined differently in both space and time; just as Japan and Argentina might have two different ideas of what constitutes as “normal”, so does 18th century and 21st century United States. We also talked about normalization, or how things become more (or less) socially accepted over time. Finally, we introduced the concept of “militarism”. In this article, we’ll attempt to define it as concisely as possible, as well as give examples of militarism in Japan.

The following statement is found in page 92 of the 1996 edition of Naval Science 1, a textbook used for High School JROTC courses.

“Our history has shown us that strength has a meaning of its own. Being right is not enough when there are countries that understand only strength. It takes might to preserve the right where nations are concerned. The power of our Navy reflects the power of the way of life it must defend, and that includes all nations that join with us in common need. If we are not a strong people with adequate naval and military forces, other countries with more strength will become the world leaders. This would end our way of life.”

Keep this statement in mind as we discuss the concepts of militarism and militarization.

Attempting to find a wholly agreed upon single definition of militarism and how it is different from militarization is complicated. Often they're used interchangeably, or delineated differently by different authors. This stems from the fact that to define either, a frame of reference is necessary:

¨...a universal definition of militarism is likely to be meaningless. No brief sentence could cover all the different consequences of military thought and action which possibly could be called militarism while effectively excluding those things which should not be given that name. There are important differences in time and place. Militarism in industrialized countries is different from that in traditional societies. Soviet militarism is significantly different from French militarism, etc. In addition, there are of course ideological discussions about the definitions and understanding of militarism at a particular time and at a particular place. “1

Why go through all the trouble of looking to define it, yet again, if, universally, it might prove to be too broad to too narrow? If a concept or idea will be used again and again, definitions save time, simplifying explanations. With that in mind, throughout this series we will use militarism to mean a philosophy, way of thinking, or attitude taken by governments and peoples where “...military capability is the most meaningful and effective instrument for achieving any and all national goals, and that soldiers, weapons and wars are the most necessary and noble tools for national protection and advancement”2 Militarization, on the other hand, is a process, accruing the tools for making war--weapons built, soldiers trained, people roused.

Is the statement which opens this article an example of militarism, or of militarization? There are two aspects to keep in mind: the ideas which it seeks to peddle (“It takes might to preserve the right where nations are concerned”), which place military strength as a goal of utmost importance and are therefore militaristic; and where this information is placed: a high school textbook in a course sponsored by the military. This points towards the process of militarization, the normalization of these ideas through the authority of a textbook, of a classroom setting. It primes the students, if not to enlist, at least to see the increase of military power and its violence as justifiable.

To further understand militarism as both the result of a historical and social process, and the driving force that can determine the future, we will try to examine it in the socio-historical context of pre-World War II Japan. As explained previously, there are boundless amounts of data, analysis, and interpretations which span long tomes and series of articles. For brevity’s sake, this exploration will be simplified to a degree. Our biggest concern is to look at an indisputably large aspect of Japanese society at that time (the belief in military might, above all) and the philosophic, ideological, historical, social and cultural which not only supported it, but that also advanced its growth and justified it.

Fukoku kyôhei, or “Rich Country, Strong Military”, a Japanese national policy from the Meiji Restoration era points to a very obvious centrality of military interests as part of the government’s goals for the nation. The Meiji Restoration was what came about after Japan’s door were forced open by Commodore Perry and his fleet in 1854, when rebels overthrew the feudal system and ended the shogunate, the warrior class government that ran parallel to the emperor’s rule. This restoration was purportedly that of the emperor, returning him to the sole ruling position inside the government. However, what really happened was that the power migrated from the shogunate to the rebels, making them the new ruling class, and the emperor remained a mostly a symbolic figure.

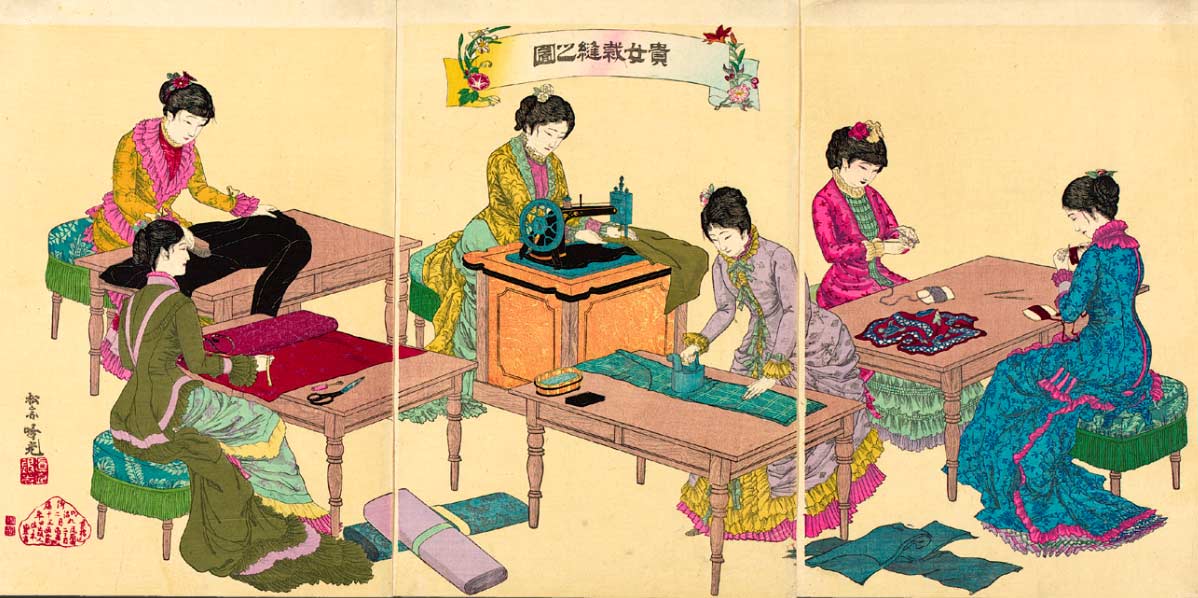

This restoration meant a whole restructuring of Japan’s political, economical, and social systems. The government focused all of its efforts to the Westernization of Japan, that is, the adoption of Western values and practices, hoping to catch up to, and eventually surpass western imperial powers at the time (Britain, Germany, America, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Russia, and Italy)4. The Meiji ruling class (the oligarchy) “...desired to join the Western powers in demands for rights and privileges in other Asian countries. However, the oligarchs realized that the country needed to modernize and strengthen its military before it attempted to assert its demands to the Western powers.”3 By the end of World War I, they had achieved this objective, finding a place as one of the “Big Five” in 1919 Versaille, where the nations that had emerged victorious attempted “...to dictate peace terms and form the League of Nations.”4

Japan achieved this by intense industrialization. As can be seen in the following prints from this time, western fashion and concepts of industry were in vogue at the time.

The prints themselves, done with techniques heavily associated with Japanese tradition and yet depicting foreign ideas intermingling with Japanese society, are reminders of the role of the arts in furthering an agenda. Important intellectuals, too, such as Fukuzawa Yukichi (who was offered a seat in the government on several occasions) traveled to these occidental nations and wrote about the customs and ways of life he observed. The philosophy which gained a lot of traction at that time was that of Social Darwinism, which was not out of place for the nineteenth century world and can be summed up by this 1880’s Japanese popular song:

In the West there is England,

In the North, Russia.

My countrymen, be careful!

Outwardly they make treaties,

But you cannot tell

What is at the bottom of their hearts.

There is a Law of Nations, it is true,

But when the moment comes, remember,

The Strong eat up the Weak. 5

Social Darwinism, in fact, is the idea of “survival of the fittest” applied to a social, as opposed to natural, context. It is the idea that those who prevail have done so out of their own strength, and are thus the best or most advanced. It no surprise that this idea could lead towards militarization; if survival, strength, and the thought that competitiveness is the natural state of things are the imperatives in a society, then it makes sense that this society would develop in ways that it fulfilled these imperatives.

In the case of Japan, many of its leaders “...came to believe that their country had a ‘manifest destiny’ to free other Asian countries from western imperialist powers and to lead these countries to collective strength and prosperity.”6 Ultranationalist groups believed in the purity of their race, and out of some supposed sense of brotherhood, wanted to lead other nations in their vicinity to what they considered was a more advanced state of civilization. (More on this can be read on Ruth Benedict’s germinal and very influential work about World War II Japan: The Chrysanthemum and the Sword). They involved themselves and started armed struggles in both Korea and China, and even emerged victorious against Russia in 1904-5, which made them confident in their own strength.

As was demonstrated by the popular song quoted above, just as they were gaining confidence in their military prowess, they feared being invaded by foreign powers as other Asian nations had been. This was not helped by other nations’ attitudes and affronts towards Japan. Prejudice towards Japanese at an international policy level, segregation towards Chinese and Japanese-Americans in the United States, and eventually the prohibition of Japanese immigration only fueled anti-foreigner sentiment in Japan.

Lastly, imperialism and gain or defense sought through military conflict were also motivated by economic reasons. Expanding their territory, the Japanese were also expanding their markets and supply chains. Eventually, the United States deciding to put up an oil embargo in the forties led to the Japanese to attack Pearl Harbor.

Seen from the perspective of historical events, the militarization of Japan can be understood as a result of many forces and pressures both from within and without its society. When analyzing Japanese society both at that time and previous to it, one could also find the fertile ground in the glorification of martial values, the Bushi code, the concept of Yamato Damashii, etc. Again, an excellent starting point for understanding Japanese society, how Americans conceive it, and how these conceptions shaped the end of the war, is Ruth Benedict’s book The Chrysanthemum and the Sword.

Using our previously defined concepts, militarism can be seen in the “rich country, strong military” slogan, as well as the many benefits and justifications that the Japanese oligarchy saw in engaging in armed conflicts. Militarization is the process in which they built up the military strength that eventually propelled them to be included as a world superpower, and be seen by others as a very real threat.

This series will contemplate these concepts not precisely from a historical perspective, but through the analysis of culture, particularly, popular culture. Popular culture is a field in which the intentions of the creators and how they are received and interpreted by vast amounts of people intermingle. As will be explained in the next article, by studying popular culture we’re not merely studying a reflection of the social context it comes from, but a creation of a social reality, of symbols and a common sense which people both inhabit and modify. Although an object of popular culture, such as a movie, TV series, comic strip, etc. seems static, its relationship with society is constantly changing. By studying both the object and people’s interpretations of it we can get a clearer picture of the underlying forces that are at work in a collective context.

The quote we saw in the beginning of the article is, likewise, the result of historical and social processes, but also justifies and drives the actions of those who believe in its veracity. Militarism is both a result and a cause. In pop culture, we see those who drive the narrative towards this conclusion on purpose, as well as how and what society accepts, appropriates, interprets and eventually furthers these ideas. War doesn’t begin when they’re making the guns or training the soldiers, but instead it starts much earlier, when a society generally agrees that armed, legal violence is the only solution to certain conflicts.

Sources

1, 2 Skjelsbaek, K. (1979). Militarism, Its Dimensions and Corollaries: An Attempt at Conceptual Clarification. Journal of Peace Research, 16(3), 213-229. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/423726

3, 4, 5, 6 Gordon, Bill. “Japan's March Toward Militarism.” Japan's March Toward Militarism, Mar. 2000, wgordon.web.wesleyan.edu/papers/jhist2.htm.

8 Dower, John W. “Throwing Off Asia.” MIT Visualizing Cultures, Massachussets Institute of https://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/throwing_off_asia_01/toa_essay03.html.

Series Homepage at http://nnomy.org/index.php/en/resources/blog/researching-militarism-selene-rivas

Selene Rivas is an anthropology student at the Central University of Venezuela and an intern for the National Network Opposing the Militarization of Youth. Contact her at srivas@nnomy.org

###

Countering Military Recruitment

WRI's new booklet, Countering Military Recruitment: Learning the lessons of counter-recruitment campaigns internationally, is out now. The booklet includes examples of campaigning against youth militarisation across different countries with the contribution of grassroot activists.

You can order a paperback version here.