Monuments and memory in Former Yugoslavia

Boro Kitanoski -

I was born in 1976. One of the first memories I have is the anniversary of the death of Josip Broz Tito, Yugoslavia’s long serving marshal, World War II hero and life-long president. It was 4 May 1981. Every year after his death, the anniversary was observed by loud sirens in all of the bigger towns in the country, announcing the full stop of all activities for a minute or so: factories, traffic, people on the streets. I remember that I had come out of the house with a handful of biscuits when the siren sounded and everything stopped. All of the other kids and adults on the street stood still. I also stood still, but the cookies in my hand were so enticing that I just had to eat them at that very moment. I couldn’t wait till the siren stopped. I remember standing absolutely still, only moving one hand to eat them. I still remember feeling that I had betrayed something and a minute after the sirens stopped, running to my uncle’s house and confessing what I had just done. Of course he laughed and comforted me, but he also was proud of me showing such respect to the dead leader.

I live in a highly militarised society. I recognise it in the mindset of people and in their relationships: families are militarised, our education and the way institutions function are militarised. Even our approach to peace is militarised (peace studies in Macedonia are under the College for Defence – formerly Peoples’ Defence Studies). Peace is a defence strategy while you are weaker - we often joke about it.

I live in a building with a big underground bomb shelter just across the street. All of the neighboring buildings have bomb shelters. In fact, just a few years ago it was a legal obligation for people building new houses to allot one room in the basement as a potential bomb shelter, with prescribed dimensions.

Education is militarised

I grew up in a strict and militarised school. Visits to army barracks were frequent and included presentations of weapons. We were taught basic survival techniques during an occupation, the detailed construction of the old M48 rifle (despite it not being in official use any more), and how to treat wounds. Many classes were fed nationalism – patriotism - especially in History classes. The lessons were single perspective, always portraying 'us' as victims of historical processes, being under constant danger from neighbours: 'they proved their aggressive politics towards us many times in the past, surely they will do it again'.

Past wars are celebrated as defensive and glorious. The more distant the war, the more positive people's views on it. However, once we are in a war, it is absolutely necessary for everyone to take part in it.

Lack of discussion on what really happens in war

We talk a lot about wars, but don’t really say much. There is no real discussion. Talk is highly emotional, full of stories about heroic behaviour and injustice against us. We don’t talk about particular cases; we almost never talk about conflicts from a different perspective. Trying to understand the 'opponent’s' perceptions is seen as enemy propaganda. The same people who made or supported the wars of the 1990s are still the most respected and often the most powerful. Young people in the Balkans today don't really have memories of what happened during the wars: they are more easily misguided and recruited to the new nationalist armed forces.

Sport has always been a big thing in the Balkans. Symbolically, the bloody collapse of Yugoslavia was once reenacted in a football match in May 1990 in Zagreb between leading clubs from Croatia and Serbia: huge clashes occurred. Years later we realised that those clashes were not really as spontaneous as they were presented as being, like many other things that followed. Sport stadiums are great public spaces for hints of politics to come. Football fans are extremely nationalistic, mono-ethnic, easy to mobilise, and supported by the state or political parties. Small armies to be.

Recruitment by the military

With a high rate of unemployment in the country, the military is seen as a secure and socially respected profession. There are very few jobs of any kind, so the high level of respect towards soldiers and the feelings of nationalism boost support for those choosing a military career. Interest in joining the armed forces is huge: they don't even have to make commercials. Young people see it as very respectable and socially-desirable career choice.

Memorials

All around the Balkans there are hundreds of new monuments built to mark the tragic events of the recent wars, despite that fact that it is illegal to build them. Just before the Darmstadt conference I was in Sarajevo, Bosnia. My friends from the Centre for Nonviolent Action were starting to research war memorials built since the 1990s. They were studying what the monuments look like, what messages they give, who they speak to, and why. Do these memorials really speak to us? Do they give a clue to what people think about the wars? Here are some examples.

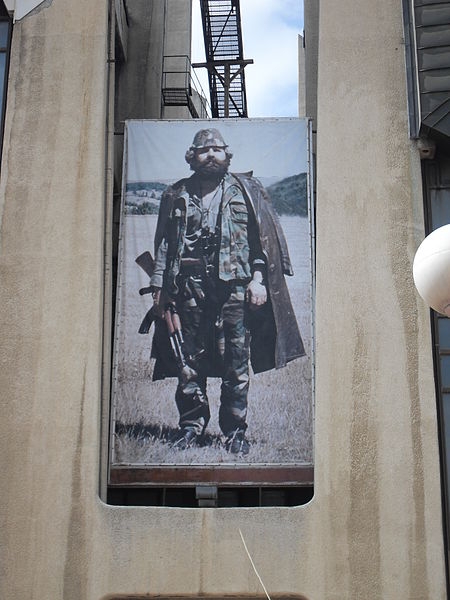

- Many memorials are statues of famous war combatants. They are heavily armed, sometimes with more than one weapon. In the village of Radusha in Macedonia, a statue of a local commander was armed with a pistol and two rifles, standing on top of a real tank that had been destroyed during the war of 2001 and allowed to remain as the base of the memorial.

A huge photo of Adem Jashari, a Kosovo Liberation commander who was killed by the Serbian Police and is considered by many in Kosovo to be a war hero in Kosovo, permanently installed in the monument outside the Youth and Sport Centre, Pristina, Kosovo, 2010 (credit - Ferran Cornellà)

- In many villages in Macedonia and Kosovo it is common to find new memorials in the local cemeteries where there are lots of graves of fallen soldiers from that village, together with civilians. In many places, even civilian casualties are presented with national and military symbols. The message is clear: they all died for the national cause. As the saying goes, 'There are no civilians in war…'

- There is a new monument in central Sarajevo to memorialise the tragic loss of over 1,500 of its children during the siege of the town between 1992 and 1996. At the base of the monument it says: 'In memory of the children killed in besieged Sarajevo'. It can be said that, as part of the town was under the control of Serbian forces and not besieged, the monument sadly excludes some of the 'other' children who also died so tragically in the town.

- A message on a monument in Srebrenica is often seen as controversial in the way it interprets revenge and justice. It says: 'In the Name of God the Most Merciful, the Most Compassionate, We pray to Almighty God, May grievance become hope! May revenge become justice! May mothers' tears become prayers that Srebrenica never happens again to anyone anywhere!'

- Many crosses, fleurs-de-lis, eagles and other national symbols - even churches and mosques - are the new marks of ethnic territory telling the one-sided stories of the recent past. Monuments are there to stay for a long time, and there is a general feeling that in many ways they are just a continuation of the war by other means. What we do about it is still uncertain.

While I was working on this article, the police in southern Serbia demolished an illegal memorial with the names of Albanian victims on it. In turn, an antifascist memorial of World War II in Kosovo, considered to be Serbian, was destroyed. The war narrative goes on...

###

Countering Military Recruitment

WRI's new booklet, Countering Military Recruitment: Learning the lessons of counter-recruitment campaigns internationally, is out now. The booklet includes examples of campaigning against youth militarisation across different countries with the contribution of grassroot activists.

You can order a paperback version here.